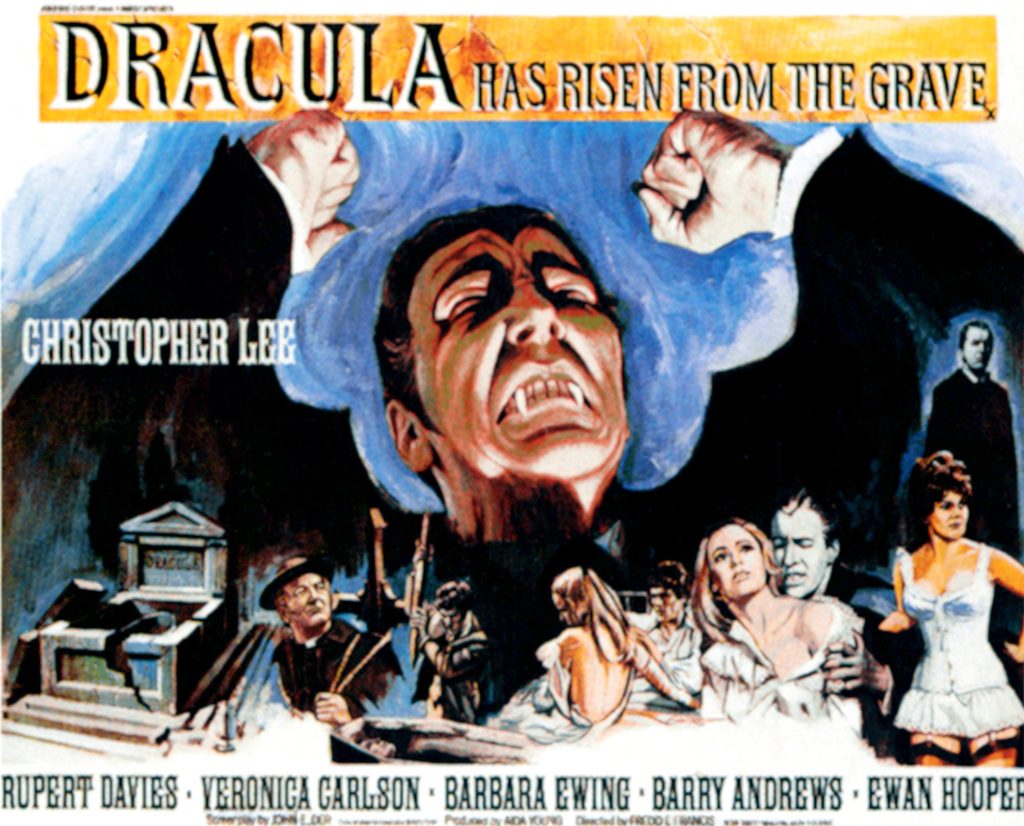

Rating: B

Dir: Freddie Francis

Star: Barry Andrews, Veronica Carlson, Ewan Hooper, Christopher Lee

I think this is probably my second favourite of all Hammer’s versions, trailing only behind the original Dracula. While it has been criticized for playing fast and loose with the mythos – in particular, pulling out of nowhere the notion that you need faith in order to destroy a vampire – I think what this adds is sufficient for me to give it a pass. We begin somewhat loosely following the footsteps of Dracula, Prince of Darkness, though the specifics are largely glossed over. We do end with the Count (Lee) entombed in the ice near his castle, though the darkness of his evil still casts a long shadow over the local town, and church inside whose bell a victim was found dangling.

The local Monsignor, Ernest Muller (Rupert Davies) vows to lift the curse by performing an exorcism at the castle, but the local priest (Hooper) accompanying him has an accident on the way, and his split blood rewakens Dracula. Rather annoyed to find his home now cleansed, the Count turns the priest into a minion, then leaves his mountain lair, in order to take revenge on the Monsignor, and his attractive niece, Anna (Carlson). The main opponent is Paul (Andrews), who is Anna’s boyfriend and a local student. However, he and the Monsignor have certain religious differences of opinion, and Paul’s lack of faith is a potentially lethal roadblock to defeating the Count, before he can turn Anna into his latest bride.

I particularly like the various approaches to religion shown here. These run the gamut from the Monsignor’s rigid and unshakeable belief, which brooks no argument. When he discovers over dinner that Paul doesn’t go to church, his first reaction is “You’re not a Protestant, are you?” The truth is even more awkward, Paul being an atheist. This sets the two at odds for the rest of the film, when they should be united against their common enemy. Meanwhile, there’s the priest, whose faith was shattered by his previous experiences, opening the door for him to become a slave to the Count’s will. It’s something a stronger soul might have been better equipped to resist.

I particularly like the various approaches to religion shown here. These run the gamut from the Monsignor’s rigid and unshakeable belief, which brooks no argument. When he discovers over dinner that Paul doesn’t go to church, his first reaction is “You’re not a Protestant, are you?” The truth is even more awkward, Paul being an atheist. This sets the two at odds for the rest of the film, when they should be united against their common enemy. Meanwhile, there’s the priest, whose faith was shattered by his previous experiences, opening the door for him to become a slave to the Count’s will. It’s something a stronger soul might have been better equipped to resist.

There’s also a nice contrast between the relatively pure, innocent Anna, and Zena (Barbara Ewing), the waitress who works alongside Paul in the local inn (Prop: M. Ripper, naturally!). She’s clearly the town slut: when Paul says “You’ve got more boyfriends than you can remember,” she replies “I’ve always got room for one more.” Naturally, Zena is easy prey for the Count, even though he’s just using her to get to Anna. “What do you want her for? You’ve got me!” she complains petulantly, not realizing Dracula has a zero-tolerance policy for minions who talk back. She’s not greatly missed, her employer waving away Zena’s absence as, “Off with some student, I suppose. Come back again in about a fortnight and want her job back.”

Helping matters here is Andrews’s performance as Paul, who is easily among the most likable of Hammer’s young male heroes – as we’ve seen often enough before, they tended to be bland, at best. Here, he’s clever and brave, if perhaps a little naive, not realizing pure honesty may sometimes be best sidestepped. His refusal to compromise his principals is laudable, though again, somewhat aggravating. Then there’s Lee, whose gravitas may never have been more forceful, commanding the audience’s absolute attention, every second he is on the screen – and looming over proceedings, even when he isn’t. The personal nature of his feud humanizes the Count, by making him someone capable of petty revenge. Though you could argue whether or not that’s a helpful development.

Arthur Grant’s cinematography is quite excellent, and the roof-top setting in which much unfolds, between the Monsignor’s house and the local inn, adds a sense of things taking place literally above the heads of us mortals. It provides a particularly effective sense of detachment, and there’s no conveniently helpful mob of villagers with torches around to assist in the finale. It comes down to Paul, the priest finally relocating his spiritual cojones, and a conveniently landed, impressively pointy crucifix, Size Xtra-Large. All very solid and satisfying, even despite the absence of Peter Cushing.

[January 2008] I’m curious to watch some of the other Hammer Draculas – particularly those involving Peter Cushing – and see how they match up to this. Certainly, it benefits from being somewhat more restrained and avoids the silliness which would tend to plague their later productions, as they strove to keep up with Hollywood. Lee also demonstrates the way a vampire should be, balancing between the sensual Eurotrash cliche of Anne Rice and the mindless eating machine: he has a feral intensity, and there’s no denying his viciousness, yet you can also see the appeal. I also thoroughly enjoyed the jabs at religious hypocrisy, as Dracula is resurrected by the blood of a priest who has lost his faith (Hooper), and subsequently strikes out for revenge against the Monsignor who sealed Dracula’s castle with a crucifix – said revenge involving the Monsignor’s (inevitably, pretty) niece. Yet, ironically, the only hope she has is her atheist boyfriend (Barry Andrews).

The most interesting character however, is Hooper’s nameless priest, who ends up becoming Dracula’s henchmen, Renfield-like. He struggles with his conscience, yet is largely powerless to resist. There is, this being Hammer, naturally a dose of reactionary conservatism, with the local slutty barmaid (Barbara Ewing) meeting a bad end; this being Hammer, that doesn’t even count as a spoiler. Carlson, playing the niece, is a natural counterpoint – blonde vs. brunette, chaste vs. wanton – though doesn’t get as much to do except climb over the rooftop sets. Francis’s strength as a cinematographer is apparent, and it’s certainly among the lushest and best-looking Hammer films, full of striking, if sometimes illogical, imagery such as Dracula’s tears of blood. Though the pacing on this seems a bit off: it takes quite some time to establish everything, and the finale is set-up, takes place and we roll credits inside about two minutes. Merely one in a series which contained a number of great films, while this remains very good, I’m probably open to being convinced that there are better ones to act as Hammer’s representative. B+

This review is part of Hammer Time, our series covering Hammer Films from 1955-1979.