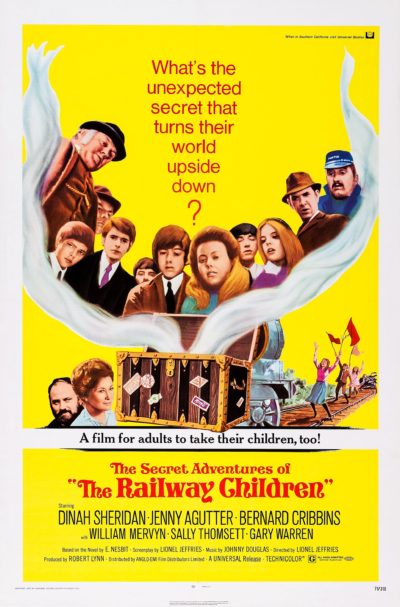

Rating: A+

Dir: Lionel Jeffries

Star: Jenny Agutter, Sally Thomsett, Gary Warren, Dinah Sheridan

Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the UK release of this, arguably the greatest “U”/”G” certificate film of all time. E. Nesbit’s classic book was first published in 1906, and has been adapted on a host of occasions, beginning with a radio version in 1943. But despite the plethora of versions – at least three of which have starred Agutter in various roles – this remains the definitive one. Jeffries first read the book while returning by boat from America, where he had been filming Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, borrowing his daughter’s copy. He loved the story and paid £300 for an option on it. EMI Films produced it, and agreed to let Jeffries direct, for the first time. There cannot have been many more successful debuts.

It’s all the more remarkable, in that it’s a film which defies cinematic convention, and unfolds without a visible antagonist. I guess the “bad guys” here are technically the authorities, who arrest the family’s father on false charges. But they’re never seen, and are more a plot catalyst. In this, it can be compared to another classic, Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro, which succeeds in similar spirit of indefatigable warm-heartedness, without any conflict. I note, both are also about a single-parent family who have to move to the countryside, where the kids operate largely independently, and experience their own adventures. The two films would make a perfect double-bill.

I mention below Nesbit’s association with George Bernard Shaw, but there’s a rather different view of class here to, say, Pygmalion, which believes the upper-class are just like us, only with better clothes and diction. The family here may “have to play at being poor for a while,” (and it seems quite a comfortable version of poverty, at that) but they remain resolutely upper middle class in their attitudes and behaviour. They may be happy to associate with the locals, yet it’s notable that, when the problem of the patriarch needs to be addressed, it’s one of their ‘own kind’ who provides the solution, in the shape of the “old gentleman.” My PhD thesis on The Socio-political Subtexts Incorporated in The Railway Children will be coming soon, to a polytechnic near you…

I mention below Nesbit’s association with George Bernard Shaw, but there’s a rather different view of class here to, say, Pygmalion, which believes the upper-class are just like us, only with better clothes and diction. The family here may “have to play at being poor for a while,” (and it seems quite a comfortable version of poverty, at that) but they remain resolutely upper middle class in their attitudes and behaviour. They may be happy to associate with the locals, yet it’s notable that, when the problem of the patriarch needs to be addressed, it’s one of their ‘own kind’ who provides the solution, in the shape of the “old gentleman.” My PhD thesis on The Socio-political Subtexts Incorporated in The Railway Children will be coming soon, to a polytechnic near you…

Yet such things are, very clearly, secondary. While the other versions of the story are perfectly serviceable, there’s something about this one which elevates it to a higher, almost mystical plane. It was, quite deliberately, made by Jeffries as a counterblast to liberalism, the director saying, “I knew we were taking a big, calculated risk in swimming against the permissive mainstream with such a story.” And it still stands that way today: it can be seen as providing a ringing endorsement of the often-mocked notion of “family values,” in which fidelity and love will inevitably triumph over all obstacles. The setting may be archaic, yet those principles are ones which resonate down through the decades to modern viewers. Even those with the steeliest of hearts will probably find themselves with an urge to call their fathers as the final credits roll, with the cast waving us goodbye.

[February 2010] Yeah, I know. The same man whose 2009 movie of the year was Martyrs, gets all gooey-eyed over a U-rated film made forty years ago. But it never fails: it’s just about perfect at what it does, and may be the finest debut feature by a director of all time. And what it does, is evoke an era of unremitting goodness, where no-one was ever cruel or unkind, and things always turned out for the best. It is, of course, completely unrealistic, but Jefferies and his team doing a miraculous job of creating such a universe, and making the viewer buy in to that. And there’s no alternative, since there are really no protagonists outside the three children. They, and their mother, have to move to Yorkshire after the father is arrested for espionage. There, after a dicey start, they befriend the locals and an old gentlemen on a passing train, who waves to them every day. Can he also help them get re-united with their father?

Well, if you’ve seen this, you’ll know the answer to that – and the phrase “Daddy, my Daddy!” will probably be sufficient to send you into a sniffling ball, regardless of age. For this is not just a film for children, but about childhood, and growing up, and so can be enjoyed by anyone whose heart is not completely made from stone. It’s very faithful to E. Nesbit’s classic story, even taking across the Socialist undertones (Nesbit was an associate of George Bernard Shaw), as revealed by both the Tsarist refugee, and the basic plot of a wrongfully imprisoned man. However, it is beguilingly class-unconscious; Bobbie (Agutter) describes her family as “ordinary,” despite the multiple servants that inhabit their house. Such things are very, very subtly handled, however. It helps that the lead actors and actresses are great, even if both Agutter an Thomsett are much older than the characters they portray – the former had just finished shooting the not-so family friendly Walkabout, while the latter was aged twenty at the time, and apparently had a clause in her contract not to be seen drinking or smoking during filming. If they’d been making To Catch a Predator at that time, she’d have been an ideal lure.

The supporting characters are equally as good. In the viewing for this piece, Sheridan’s grace and poise as mother was particularly outstanding, as she tries to keep the horrors of everyday life away from her children, and provide them with a strong moral core. The cinematography and setting are similarly wonderful, and it all combines in a way calculated to make even the most hard-hearted and cynical exploitation fan – and, in the rest of my life and 99% of my movie choices, I stand guilty as charged – regress to an age of innocence, without engaging in cloying sentimentality. Everyone has a weak spot, and I’m not ashamed to admit that this film is mine. A+